23 Aug Islam & Yoga

Yoga has traversed diverse cultural landscapes, gaining recognition and adaptation far beyond its origins. Among the various religious and intellectual traditions that have engaged with yoga, the Islamic scholarly tradition stands out for its nuanced and multifaceted interaction.

The relationship between Islamic scholars and yoga is not merely a historical footnote but a rich intellectual exchange, cultural adaptation, and spiritual exploration.

This article delves into the history of this interaction, tracing its evolution from the early centuries of Islamic expansion to the present day, examining the ways in which Islamic scholars have interpreted, adapted, and sometimes contested the practice of yoga.

Early Encounters: The Expansion of Islam into India

The earliest encounters between Islamic scholars and the practices of yoga occurred during the expansion of Islam into the Indian subcontinent, beginning in the 7th century CE. As Muslim armies, traders, and mystics moved into India, they came into contact with a rich variety of religious and philosophical traditions all of which had various interpretations and practices of yoga.

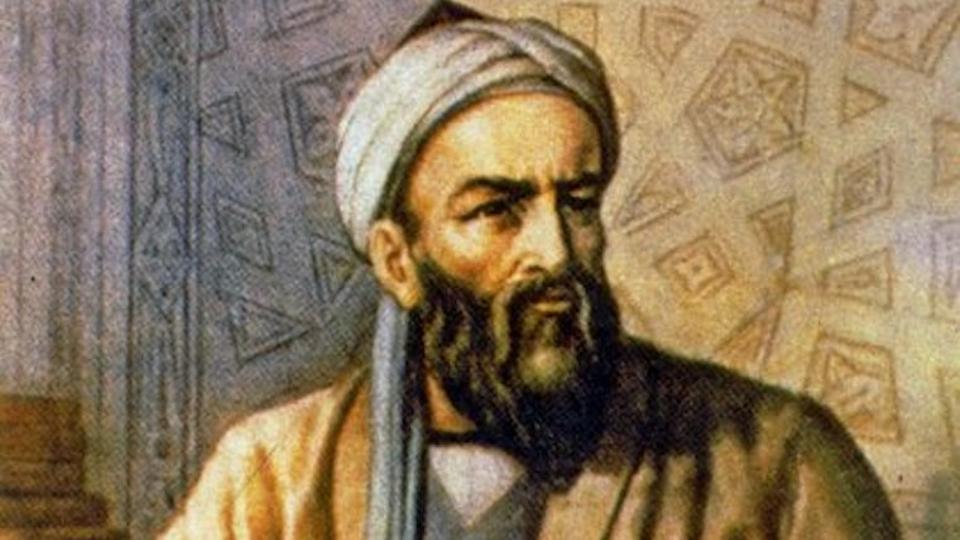

One of the earliest records of Islamic interaction with yoga can be traced to the works of the Persian scholar and traveler Al-Biruni (973–1048 CE, pictured above). Al-Biruni was one of the first Muslim scholars to study Indian culture extensively, and his writings provide a detailed account of Hindu philosophy, including yoga. In his seminal work, Kitab al-Hind (The Book of India), Al-Biruni offers a comprehensive description of the practice of yoga, emphasizing its spiritual and philosophical dimensions.

He recognized yoga as a profound system of spiritual discipline, aimed at achieving union with the divine. While Al-Biruni did not adopt yoga as a practice, his objective and respectful engagement with it set a precedent for later Islamic scholars.

Sufi Mysticism and the Adaptation of Yogic Practices

The most significant interaction between Islamic scholars and yoga occurred within the mystical tradition of Sufism. Sufism, with its emphasis on inner purification and the direct experience of the divine, found certain aspects of yoga, particularly its meditative and ascetic practices, to be resonant with its own spiritual goals.

From the 12th century onwards, as Sufi orders began to establish themselves in India, there was a noticeable synthesis of Islamic mysticism and yogic practices. Sufi saints such as Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti (1141–1236 CE), the founder of the Chishti Order in India, are known to have engaged with yogic practices, particularly those that involved breath control and meditation, which were seen as methods to attain spiritual enlightenment and proximity to God. These practices were often adapted and Islamized, with a focus on the recitation of divine names (dhikr) and the contemplation of Quranic verses, integrated into the broader Sufi spiritual framework.

One of the most illustrative examples of this synthesis is the Amritakunda (The Pool of Nectar), a text that is believed to have been composed in the 13th century. The Amritakunda is a fascinating work that blends Islamic mysticism with yogic teachings, presenting yoga as a path to spiritual realization within an Islamic context.

The text was widely circulated among Sufi circles and was later translated into Arabic, Persian, and even Turkish, reflecting its broad influence. The Amritakunda demonstrates how certain yogic practices, such as breath control (pranayama) and bodily postures (asanas), were reinterpreted and integrated into the Sufi tradition, often with a focus on achieving states of divine ecstasy (wajd) and spiritual union (ittihad).

Philosophical and Theological Debates

While some Islamic scholars and mystics found value in yogic practices, others approached yoga with caution or outright skepticism.

Despite these critiques, scholars sought to reconcile the spiritual goals of yoga with Islamic teachings. The 16th-century Mughal prince and philosopher Dara Shikoh (1615–1659 CE) is a notable example. Dara Shikoh, deeply influenced by Sufism, sought to bridge the gap between Hinduism and Islam through his scholarly works.

In his seminal work, Majma-ul-Bahrain (The Confluence of the Two Seas), Dara Shikoh explored the commonalities between Islamic Sufi mysticism and Hindu philosophy, including yoga. He argued that the essence of yoga, particularly its emphasis on inner purification and divine union, was compatible with Islamic teachings, and he sought to create a dialogue between the two traditions.

Colonial Period: Yoga and Modernity in Islamic Thought

The advent of British colonialism in India in the 18th and 19th centuries brought new challenges and opportunities for the interaction between Islamic scholars and yoga. The colonial period was marked by a heightened awareness of cultural identity and religious boundaries, leading to both the defense of Islamic tradition and the exploration of new ideas, including those related to yoga.

During this period, some Islamic reformers viewed yoga with suspicion. However, others, particularly those influenced by the growing interest in spiritualism and theosophy in the West, began to view yoga as a universal practice that transcended religious boundaries.

One of the most significant figures in this regard was the Indian Muslim scholar and reformer Syed Ahmed Khan (1817–1898 CE). Syed Ahmed Khan, the founder of the Aligarh Movement, was a proponent of modern education and sought to reinterpret Islam in light of contemporary knowledge.

While he was cautious about adopting practices from other religions, he was open to the idea of engaging with yoga from a scientific and philosophical perspective. He saw the potential for yoga to contribute to physical and mental well-being, provided it was stripped of its religious connotations.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries also saw the emergence of Islamic scholars who sought to present yoga in a way that was compatible with Islamic teachings. An example is Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938 CE), a philosopher, poet, and politician who is considered one of the intellectual fathers of Pakistan.

Iqbal was deeply interested in the concept of the self (khudi) and spiritual development, themes that resonated with certain aspects of yoga. While he did not advocate for the adoption of yoga per se, Iqbal recognized the value of self-discipline and inner strength, qualities that are central to both yoga and Islamic spirituality.

Yoga in the Contemporary Islamic World

The interaction between Islamic scholars and yoga has continued into the modern era, shaped by globalization, the rise of interfaith dialogue, and the increasing popularity of yoga as a global phenomenon. In the contemporary Islamic world, views on yoga are diverse, reflecting the broader spectrum of Islamic thought.

In some Muslim-majority countries, particularly in South Asia, yoga is practiced by Muslims as a form of physical exercise or as a means of stress relief, often divorced from its religious origins. In countries like Indonesia and Malaysia, yoga classes are popular among urban Muslims, although there are ongoing debates about the appropriateness of Muslims practicing yoga, given its Hindu roots.

Despite these challenges, there are also contemporary Islamic scholars and thinkers who advocate for a more nuanced approach to yoga. They argue that the physical and mental benefits of yoga can be appreciated by Muslims, provided that the practice is adapted to align with Islamic principles. For example, some Muslim yoga practitioners substitute traditional Sanskrit mantras with Quranic verses or the names of God (dhikr), creating a form of yoga that is spiritually meaningful within an Islamic framework.

Conclusion

The history of the interaction between Islamic scholars and yoga is a testament to the complexities of cultural exchange and religious adaptation. From the early encounters of Islamic scholars like Al-Biruni, through the integration of yogic practices into Sufi mysticism, to the modern debates about the place of yoga in the Islamic world, this history reflects a dynamic process of interpretation, adaptation, and dialogue.

While there have been moments of tension and controversy, the broader trajectory of this interaction reveals a willingness among many Islamic scholars to engage with yoga in a way that respects both the integrity of Islamic teachings and the spiritual insights of other traditions. As the global popularity of yoga continues to grow, the dialogue between Islam and yoga is likely to continue, offering new opportunities for understanding and collaboration between these two rich and diverse traditions.

No Comments